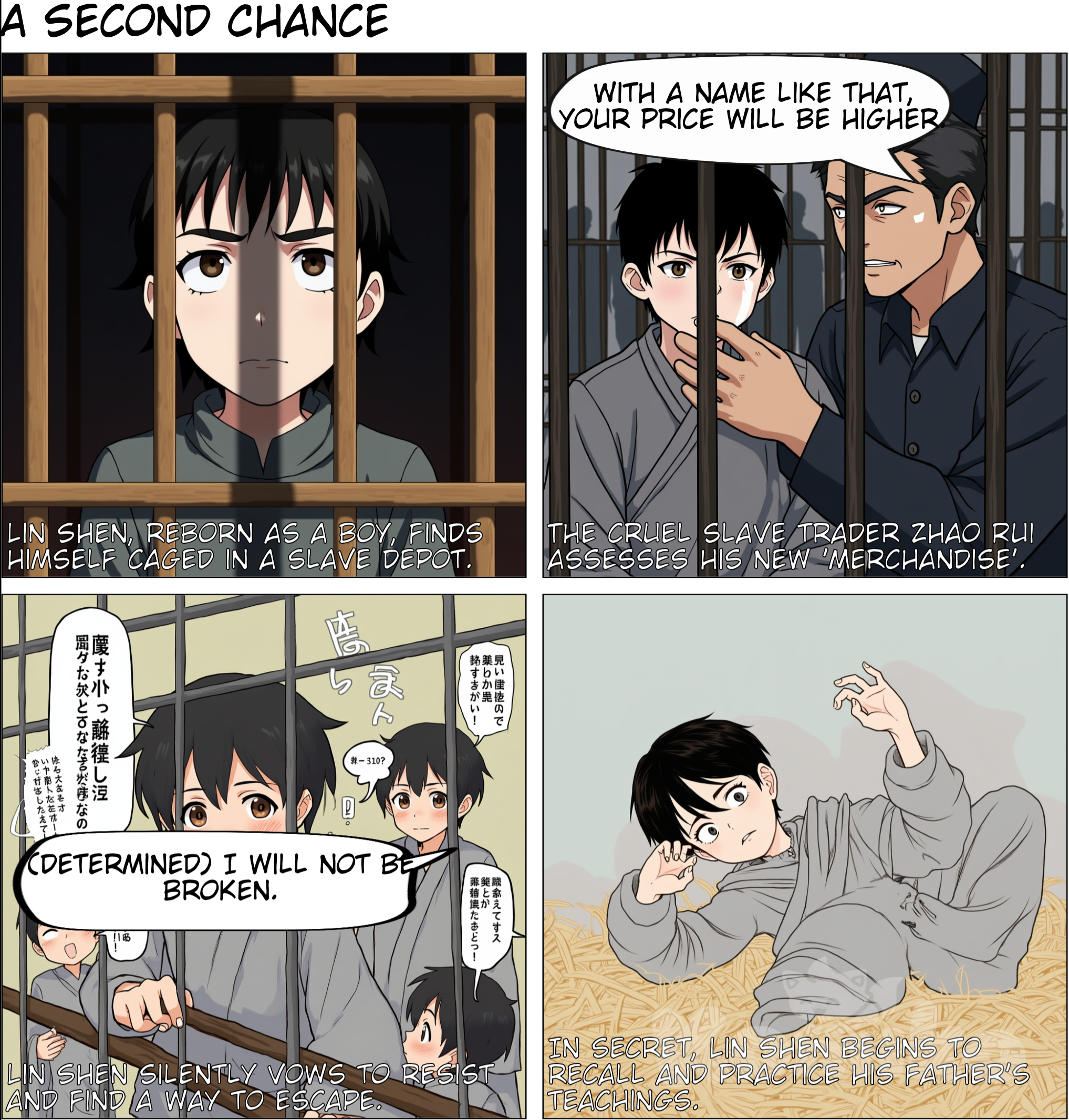

KI-Kunst: Chapter One — The Cage Beneath the Moon In the low-built town that crouched against the border like a watchful dog, discipline was not a philosophy but a weather. It seeped into every joint of the houses, threaded through the creak of the carts, and gathered at the soles of men’s boots. Lin Shen learned to measure his days the way a soldier measures march: by the repetition of tasks, by the fine abrasion of routine until one’s character was rubbed smooth and bright. From the time his bones were still soft and the world a bluff of edges, the rhythm of training remained with him—an unspoken metronome that set the pace of his heartbeat. His father, Lin Qiao, was the keeper of that rhythm. Known to many as a stubborn craftsman of a blade and stranger techniques, Lin Qiao had been a soldier in another season of the world and had kept the temper of that life in him like a secret fire. He had taught not for glory but for survival, and his instruction took the shape of small mercies and hard corrections: the way a palm could find a neck’s soft seam; the lesson that a cloak could be a shield; that a cartwheel could become a fulcrum and a farming hoe a spear. He called his method Tracesong Craft—a name as much a poem as it was an instruction—because his way was to listen to the world’s traces and answer them as one answers a song. Lin Qiao’s hands were rough as split wood; his voice was thin as a reed but it carried the steadiness of rock. He taught with proverbs that sounded at once simple and profound. “Martial skill,” he would say as he wiped dirt from a wooden dummy’s arm, “is the language of place. Learn the accent of where you stand.” “Ambidexterity is clarity,” he told his son one winter morning when the yard glassed with frost. “A hand that refuses to learn will betray your life for vanity.” Lin Shen imitated everything. A child’s imitation becomes a habit, and habit becomes an instrument. He would wait at the edge of the yard while the master students—men with callused palms, women with a soldier’s stance—practiced. He watched the way one man slipped his weight into a sweep and how another used a cart’s axle to change an opponent’s center. He would try, again and again, until his limbs found the rhythm of the movements and the pattern embedded itself beneath the skin. There was a humor that lightened the lessons. On mornings when the soup was thin and laughter thinner still, Lin Qiao would hand the boy a chisel and tell him to carve a practice shield from a piece of old wood until his hands ached and the wood shone. “A neglected arm is like a forgotten promise,” he would say, and then press the child’s elbow so he could feel the tension of proper balance. The jokes were the cord that kept stern instruction from remaking them into mere machines. The leather-bound book that sat in a small chest on the highest shelf of their home was not for display. When Lin Shen came of age to stand loose in his father’s shadow and wear shoulders that earned the respect of older boys, Lin Qiao opened that book and pressed it into his hands. “This is not the last of me,” the father said with a voice lined by seasons. The pages were thin with handling; diagrams had been sketched into margins and annotations hugged the margins like second thoughts. It smelled of smoke, oil, and the quiet memory of long practice. Within it were the arcs and knots of Tracesong Craft: ways to make a ox-cart a trap, how to leverage a farmer’s chain as a garrote, the balancing of breath with the timing of a throw. It was a map not only of fighting but also of surviving where the world was poor in mercy. “Plant it where it feeds you,” Lin Qiao instructed. “And feed it with restraint.” The border regiment took Lin Shen the way seasons took a river—inevitable and without ceremony. He left the village with the leather book folded inside his pack and his father’s words lodged in his ribs like a warm stone. The regiment was a different kind of school: harder, without the charity of humor. There were drills at dawn that had the cadence of a prayer—march, stance, fall, rise. Men who could not keep up were left to the frost. Under the leaden sky of those months he learned to move with the cold precision of one who needs to make every movement count. The battlefield is itself an honest instructor. It pays no attention to honorifics or to sentiment; it rewards only what is useful. Lin Shen found that his father’s improvisations fit the brutality of that world. When ambushed in a ruined farmhouse, he used a broken chair as a lever, breaking a man’s wrist and using the momentum to fling the attacker against a wall. When supplies tipped on a narrow mountain pass and attackers rushed to capitalize, he made the scant wreckage into a fulcrum and turned enemy positions into stepping stones. He was swift; he was inventive. Comrades came to rely on his cunning, and in rare, quiet moments they called him practical—an epithet he accepted without pride. Grief sometimes enters a life like the shadow of a passing roof—subtle, then entire. It came for Lin Shen in a letter: a narrow sheet of paper inked with the terse marks of the regiment’s administration. Lin Qiao had been caught in a raid; a caravan had been taken and fires had burned where villagers had once stored grain. The news hit him like an ax into standing wood—clear and cruel. Lin Shen returned home with a soldier’s gait and a hollow that could not be filled by rituals of condolence. The dummy stood where his father had left it. The yard kept the same echo of footsteps, but the house contained less of soul than it had the day before. Neighbors that had once crossed thresholds to train in his father’s yard now crossed the street. People who had laughed at Lin Shen’s jokes in the mess hall lowered their eyes. A town that had been a small sun in his life became a faster-moving shadow, and in that shadow the cost of survival was the quickness to desert anything that might draw danger. He felt the world contract around him until only the leather-bound book remained constant in his grip. Violence carved its slow progress. Bandits—three brothers who had been more rumor than flesh—grew bold: Gao, Peng, and Luo. They told the countryside that lawless men could take what governments would not protect. They moved like a stain, at once petty and cruel. In one cold night, their hands broke into his house. Lin Shen fought by the rule his father had taught: with improvisation as your ally. He used the splintered chair, a thrown pot for distraction, the very threshold of his home as a lever. He killed a man with the practiced precision of discipline loose from ceremony, and the act left him with neither triumph nor clean peace—only the heavy, rusted truth that the world would not stop asking for more. When the men left, they had taken the book with them in the jostle of the raid. It was like having the last thread of a tapestry torn from one’s hands. Lin Shen spent nights with fingers slick on oil, feeling the absence of what had once been warm and true as if he had lost a limb. He kept training in the dark. The frost took the shoulders of his young frame and left him with calluses as if to proof him against the future. He set snares, he studied the tracks of beasts, he learned to bind a rope with a hand that moved without thinking. Hunger sharpened his faculties into a new instrument. He moved through the months like a man learning to survive on a diet of small, precise choices: when to approach and when to lie low, when to strike and when to leave the blood to congeal in silence. And then the world decided to see how much he could bear. A note, pressed through the crack of a door like a verdict, demanded he leave. Intimidation, not argument. He tacked it to a wall as if posting a small law. He read it three times and the letters did not rearrange themselves into mercy. The bandits came again—bigger, angrier, with more hands for demolition. Doors were battering rams. The town that had once given him humanity gave instead to the currency of fear. Men who had been neighbors slowly bared teeth rather than hands when the struggle touched their thresholds. In the last tempest Lin Shen faced, the night was a blanket of gray with no stars. Men came with practiced cruelty; their attacks were a choreography of violence. He stood with his subordinates—three youngsters who had learned under his direction, their eyes still large and undulled—and together they met the raid. The skirmish tasted of blood and iron and the unpredictable geometry of desperate men. The sound of combat is a language without dialects. It rang out in small, terrible syllables: a snapped twig, a grunt, the metallic ring of a blade finding bone, the slick whisper of gore on cloth. Lin Shen moved as his father had taught him to move when improvisation is law: he used a fallen beam as a pivot to upend an enemy’s balance, found a broken spear and used its shaft with both hands so that ambidexterity became a doubling of force. He turned his left to a right without ceremony, and enemies who had planned for the expected found their plans unglued by unpredictability. His subordinates fell like struck reeds. One, a lanky youth named Bo Jian who had a laugh like boiling water, took a blade across the shoulder and went down with his hand pressed to the wound as if to hold back the shape of it. Another, young Han Jun, a solid man with the rough hands of someone who could mend a cart, had his thigh shattered by a cleft of iron. Their faces, in their last seconds, were not clouded by the world’s betrayals. They were simple—consternation at pain, the quick flash of fellowship, a regret at all the things one does not say before the light moves out. There was a fierceness to Lin Shen that the world would later remember, but in that moonlit scrub it had the shape of necessity. He executed a series of moves that later would be inked in memory as reckless brilliance: a feint to the right with his left hand while his right elbow arced in a surprising cross, a low sweep that caught an enemy mid-lunge, an improvised throw using the sling of a cart that slammed a man hard into a stump. He moved like someone who had been taught to shape the environment into the weapon of his choosing. In the end he stood alone amid the smoked-out ruins of the encounter, his breaths thin as a bell’s toll. Two men lay broken and still; black stains darkened the leaves beneath them. His own body had become a ledger of punishment: ribs that answered each breath with pain, a shoulder that hung like a poorly-strung lattice. Yet a small, stubborn flame of absurd pride burned in him—he had protected what he could, he had made his skill mean something. It was then, when the world narrowed to the distribution of breath, that he saw the shadow. Not tall—tallness is a human measure—this figure was a blot of absence under the moon, draped in garments that refused to give edges. The air around it felt different, thick as if the night had pressed itself onto his skin. The figure’s appearance was not accompanied by a sound but by a weight: the sense that some new law had shifted in the world’s statute. “Lin Shen,” the voice said, and the name arrived calibrating his bones. It was not a voice from the throat so much as a current through the marrow. His last faculties insisted on stubborn normalcy. “Who are you?” he asked, though his mouth tasted of iron and his limbs protested with the honest rebellion of defeat. The figure did not answer with a name. It laid a thing into his hand—brown as old bark and small, as if some origami of fate had been folded for him alone. The leather-bound book. For a breath the world became a careful, precise geometry of infinite tenderness and infinite cruelty. Lin Shen clutched the book as a drowning man clutches the last plank. “Do you understand exchange?” the figure asked then. Its words were not cruel but they were not friendly either. It spoke as one who cataloged balances. “I… I do not bargain with shadows,” he managed, though his voice was a thread. “You bargain every day with life,” the figure replied. “You spent leather and sweat; you paid with blood and loss. A life is but an entry. Will you add another line?” The idea was savage and simple. Offerings to such a thing are never wholly clear. Before the last moment the soldier in him—conditioned to decency in action, not sentiment—made a decision that felt like both logic and prayer. He closed his fingers around the thing the figure extended, felt it pulse faintly like a heartbeat, and understood that the moment for refusal had already passed. Darkness accepted him like an old debt. When he opened his eyes, the world was different. The change was not merely physical but instrumented in every sense. His skin felt thinner in a way that made breath loud; his limbs took on a softer awkwardness. His teeth did not bite with the habitual grit of a man hardened by years. Confusion was a small, sharp bird in his chest. He blinked against the bright absence of direct sunlight—the roof above him slatted and the light came through in stripes. He was in a wooden cage, the smell of sweat and stale bread thick and almost suffocating. Sounds—small, human—murmured around him: a cough, a child’s whimper, someone sobbing in a hush. There were other cages, clustered under a low rafters’ roof, the whole place smelling of commerce and hunger. Panic surged like a flame in his throat and he rose in something close to a bound that showed more practiced reaction than the years of a child. He placed his palms against the bars and felt metal bite his skin; they were thin and cold and the motion made his muscles protest in a youthful way. A laugh escaped him—high, surprised, and brittle. He had no right shoulder to bear with the same steadiness as before. He had not been given an old soldier’s body but a boy’s—fourteen years old, the number an absurdity and a wound. Around him the captives moved like a slow, pained tide. Eyes pinned to him—curious, tired, wary. A girl about his age sat with knees hugged to her chest; her face was thin and her eyes were like knives tempered in silence. An old man with a beard more white than hair hummed old verses under his breath. A small, wiry boy whose ribs showed worked his jaw as if chewing anger into something useful. “Slaves,” the boy called in a small voice that sounded foreign to Lin Shen’s inner ear. “Picked up near the road. Market day soon.” It took a breath to acknowledge the word as if the syllable itself carried a new weight. Slaves. The notion slipped into him like a sled into snow: solid and terrible. The leather book—the thing the figure had given him in the forest—lay not in his hand but in a place behind the membrane of memory, like a candle under a jar. He could sense its presence, the echo of its lessons, but not its leather. The knowledge, however, had lodged in his marrow. He could still recall the arc of a wrist lock, the feel of a sweep’s timing. The body had changed but the mind had not entirely forgotten. The depot swarmed with those who trafficked in human commerce. Men in rough coats, faces like stone tablets, shuffled through the aisles. Their laughter had no softness; their tasks were the registry of profit. A scarred man with a long white line across his cheek—Zhao Rui—strode in with a gait that spoke of someone for whom cruelty was a craft practiced to perfection. His eyes assessed the cages like a merchant rates bolts of cloth. Bai Kuan, a merchant with the soft thread of polite speech and the hardness behind it, came behind, running his fingers over wrists and chins and the shoulders of the captive as if he were measuring the worth of a horse. He made small notations on a blackened ledger and smiled like a man at a private joke. Around him, men with the arrogance of those whose hands are never called to honest labor cracked whips against the rafters. The Three Brothers—Gao, Peng, Luo—moved like clichés made flesh: rough, cruel, and practiced in the pleasure of a quick break of someone else. Lin Shen’s first contact with the depot’s men came in the form of a shove. A small boy—Xiao Bao—defied a slaver’s touch, and hands descended to punish him for insolence. Small flames of resistance flare in such prizes sometimes, and Xiao Bao ran at the man with a broken piece of a wooden plank. The slaver laughed at the audacity and raised a boot. Before he could put that boot down, Lin Shen—a shell of a boy but with a soldier’s observation—acted by muscle memory and the scraping of instincts. He wedged his shoulder into the bars, used his frame as a pivot, and shoved with a force surprising for his apparent age. The slaver staggered and fell with a clatter that hushed the room for an instant. For an ephemeral moment, the depot was an animal holding its breath. “Youngster!” Zhao Rui bellowed, annoyance reddening his face as he recovered. He strode forward and, with the confidence of one used to breaking others, reached through the bars to seize the boy’s chin. His fingers were like clamps, intrusive and owned. “Name?” the slaver asked, as if names were ledger entries. “Lin Shen,” came the answer—thin, decisive. It felt like a small bell struck in a nearly abandoned hall. Zhao Rui sneered. “With a name like that, perhaps your price will be higher.” He grinned in the way a man smiles when he is certain the knife will sell. He smacked the bar with his palm, enjoying the sound. Somewhere in the cages a woman sang under her breath to still a child’s fear. Old Zhang—the gray-bearded scholar-like figure that had been passed about the cages—muttered a verse about brokers of human doom and marked the sound of Lin Shen’s voice like a coin he had not yet seen. Mei Hua, the quiet girl whose eyes were quick as a hawk’s, watched the new boy as if reading his palms. There are faces that betray the presence of more than one life in them; Old Zhang’s was one such face. He saw things in the bones of men and cats and in the way a child’s jaw clenched that others did not. The depot stormed into a small violence. Men struck with whips, gripped by the ease of a practiced order. A slaver tried to teach Xiao Bao his place and the boy snarled and struck back with a swing that deserved better. The Three Brothers moved to punish him with the muscle of rage. For the price of showing defiance, many of the cage’s children would pay hard. Lin Shen did not step between every blow. He had learned restraint under his father’s hand. Strength revealed itself not as a series of heroic acts but as the quiet management of danger until the right opportunity flared. Yet when a slaver raised a wooden rod to strike Xiao Bao cruelly, the boy’s small face contorted and the world’s blood rose in Lin Shen as if a spring had been pierced. He lashed out through the bars with a practiced twist, grabbed the man’s wrist, and with a motion that spoke of years of applied leverage he snapped it. The man howled and dropped the rod like a broken bell. That instant gave the captives a breath. Old Zhang clapped a hand to his mouth and wept softly; Mei Hua’s eyes widened and then softened in an unreadable way. The slavers, enraged at their bruised pride, rallied. They were not men of much honor, but they were men practiced in restoring the order of cruelty. Fear and beatings followed; ropes were pulled taut and wrists found new ache. When the chaos subsided and the depot resumed its humming of bartering and list-making, Zhao Rui glared at Lin Shen with a look that was less anger and more an effort at calculation. “He fights like one trained,” he said to Bai Kuan, who smiled and set down his ledger with a thoughtless grace. “Keep him—some buyers will prefer spirited stock.” It was an admission of utility, not worth. He did not know yet whether to see Lin Shen as entertainment or as danger; a spirited captive could fetch a higher price if broken properly, or, if left untamed, cause losses. Lin Shen lay awake that night on a pallet of straw, the depot’s breath moving like a tide in the rafters. He turned the motion of his body slowly, feeling the aching of ribs that were not yet broken nor yet healed. His memories—harsh and bright—rolled like tide-lines. He saw scenes with the sharpness of someone who has been honed by experience: his father’s hand pressing his elbow, the way a cart’s axle could be used as a lever, the burning taste of blood at the corner of the mouth. He tasted the forest’s iron and the figure’s silence. The bargain he had made remained a mystery folded into his bones. Mei Hua came to his bars without sound in the last hours, her movement that of a practiced shadow. She had a small scrap of bread, offered with a trembling hand. “Eat,” she whispered. “Do not look at me. If they see pity, they will sell it for coin.” Lin Shen took the bread with a caution he had not known he could still feel. The warmth of it in his mouth was a small, private miracle. He watched the girl’s face—sharp angles softened by hunger—then he gave her a look that was equal parts gratitude and calculation. She turned her head away, hiding the quickness of emotion, because in that place to be seen was sometimes to be priced. Old Zhang, who kept to himself but had the habit of watching as a scholar watches a text, said in a small voice that seemed older than the rafters, “You are not like the rest of them, boy. You bear an old tune.” Lin Shen considered the phrase. “An old tune,” he repeated. The memory of his father’s lines—“Martial skill is a language of the world; learn the silence between words”—settled over him like an old coat. In the cramped and filthy depot it was easy to believe that the whole world had become a narrow ledger of trades and bargains. Yet within that ledger, within those small exchanges, a man could begin to gather another kind of wealth: knowledge, patience, the shaping of will. When the gray of dawn leaked through the slats, the depot emptied with the clatter of men preparing wares. Buyers would come with their ledgers and their cold smiles, and people like Bai Kuan would judge the currency of human flesh with the same lightness as they judged fabric. Lin Shen watched the men leave and felt the small, mechanical motion of his breath. He had been given a second life at a cost he did not yet understand, in a body that begged for nourishment and which would need to grow into the shape of danger again. He made a promise to the small circle of souls within those cages: not a shout of vengeance, but a plank of will laid quietly. He would learn this world’s measure and bend it. He would make the knowledge of the leather-bound book his, even if it was lodged for now like a seed beneath his tongue. He would not be sold wholly as a thing nor made to bow forever to the ledger. “Father,” he murmured to a sky that did not hear, the name sounding small in the rafters, “I have been given more time. I will not waste it.” There is a hardness that comes when a man has been taken to the roots of pain and offered a new graft. It is not always a sword. Sometimes it is a patient counting of breath and the steady, careful practice of small arts. Lin Shen lay awake and counted breath—one, two, three—letting the rhythm of his name return like a tide. The depot’s sounds became a lullaby for the kind of resolve that does not glitter: the chorus of feet, the rustle of ledgers, the soft complaining of straw. Outside, the world turned with the indifferent precision of seasons. Inside, in a cage beneath the moon and the rafters, a boy named Lin Shen folded his hands, practiced the first, secret motions of Tracesong Craft he remembered, and listened to the echo of a shadow’s bargain beat inside him like a second heart. Thus, the first night of his second life passed itself over him like the slow turning of a page. What had begun as an end had become the opening of a long, slow work: to learn, to survive, to shape memory into instrument. Unknown to those who bartered and laughed and ruled by ledger, a storm had started beneath one thin chest. The world was not yet aware that in the cramped geometry of a slave depot something sharpened like a blade.

Erstellt von

Inhaltsdetails

Mediendetails

Nutzerinteraktion

Über dieses KI-Werk

Beschreibung

Erstellungseingabe

Engagement

Chapter One — The Cage Beneath the Moon In the low-built town that crouched against the border like a watchful dog, discipline was not a philosophy but a weather. It seeped into every joint of the houses, threaded through the creak of the carts, and gathered at the soles of men’s boots. Lin Shen learned to measure his days the way a soldier measures march: by the repetition of tasks, by the fine abrasion of routine until one’s character was rubbed smooth and bright. From the time his bones were still soft and the world a bluff of edges, the rhythm of training remained with him—an unspoken metronome that set the pace of his heartbeat. His father, Lin Qiao, was the keeper of that rhythm. Known to many as a stubborn craftsman of a blade and stranger techniques, Lin Qiao had been a soldier in another season of the world and had kept the temper of that life in him like a secret fire. He had taught not for glory but for survival, and his instruction took the shape of small mercies and hard corrections: the way a palm could find a neck’s soft seam; the lesson that a cloak could be a shield; that a cartwheel could become a fulcrum and a farming hoe a spear. He called his method Tracesong Craft—a name as much a poem as it was an instruction—because his way was to listen to the world’s traces and answer them as one answers a song. Lin Qiao’s hands were rough as split wood; his voice was thin as a reed but it carried the steadiness of rock. He taught with proverbs that sounded at once simple and profound. “Martial skill,” he would say as he wiped dirt from a wooden dummy’s arm, “is the language of place. Learn the accent of where you stand.” “Ambidexterity is clarity,” he told his son one winter morning when the yard glassed with frost. “A hand that refuses to learn will betray your life for vanity.” Lin Shen imitated everything. A child’s imitation becomes a habit, and habit becomes an instrument. He would wait at the edge of the yard while the master students—men with callused palms, women with a soldier’s stance—practiced. He watched the way one man slipped his weight into a sweep and how another used a cart’s axle to change an opponent’s center. He would try, again and again, until his limbs found the rhythm of the movements and the pattern embedded itself beneath the skin. There was a humor that lightened the lessons. On mornings when the soup was thin and laughter thinner still, Lin Qiao would hand the boy a chisel and tell him to carve a practice shield from a piece of old wood until his hands ached and the wood shone. “A neglected arm is like a forgotten promise,” he would say, and then press the child’s elbow so he could feel the tension of proper balance. The jokes were the cord that kept stern instruction from remaking them into mere machines. The leather-bound book that sat in a small chest on the highest shelf of their home was not for display. When Lin Shen came of age to stand loose in his father’s shadow and wear shoulders that earned the respect of older boys, Lin Qiao opened that book and pressed it into his hands. “This is not the last of me,” the father said with a voice lined by seasons. The pages were thin with handling; diagrams had been sketched into margins and annotations hugged the margins like second thoughts. It smelled of smoke, oil, and the quiet memory of long practice. Within it were the arcs and knots of Tracesong Craft: ways to make a ox-cart a trap, how to leverage a farmer’s chain as a garrote, the balancing of breath with the timing of a throw. It was a map not only of fighting but also of surviving where the world was poor in mercy. “Plant it where it feeds you,” Lin Qiao instructed. “And feed it with restraint.” The border regiment took Lin Shen the way seasons took a river—inevitable and without ceremony. He left the village with the leather book folded inside his pack and his father’s words lodged in his ribs like a warm stone. The regiment was a different kind of school: harder, without the charity of humor. There were drills at dawn that had the cadence of a prayer—march, stance, fall, rise. Men who could not keep up were left to the frost. Under the leaden sky of those months he learned to move with the cold precision of one who needs to make every movement count. The battlefield is itself an honest instructor. It pays no attention to honorifics or to sentiment; it rewards only what is useful. Lin Shen found that his father’s improvisations fit the brutality of that world. When ambushed in a ruined farmhouse, he used a broken chair as a lever, breaking a man’s wrist and using the momentum to fling the attacker against a wall. When supplies tipped on a narrow mountain pass and attackers rushed to capitalize, he made the scant wreckage into a fulcrum and turned enemy positions into stepping stones. He was swift; he was inventive. Comrades came to rely on his cunning, and in rare, quiet moments they called him practical—an epithet he accepted without pride. Grief sometimes enters a life like the shadow of a passing roof—subtle, then entire. It came for Lin Shen in a letter: a narrow sheet of paper inked with the terse marks of the regiment’s administration. Lin Qiao had been caught in a raid; a caravan had been taken and fires had burned where villagers had once stored grain. The news hit him like an ax into standing wood—clear and cruel. Lin Shen returned home with a soldier’s gait and a hollow that could not be filled by rituals of condolence. The dummy stood where his father had left it. The yard kept the same echo of footsteps, but the house contained less of soul than it had the day before. Neighbors that had once crossed thresholds to train in his father’s yard now crossed the street. People who had laughed at Lin Shen’s jokes in the mess hall lowered their eyes. A town that had been a small sun in his life became a faster-moving shadow, and in that shadow the cost of survival was the quickness to desert anything that might draw danger. He felt the world contract around him until only the leather-bound book remained constant in his grip. Violence carved its slow progress. Bandits—three brothers who had been more rumor than flesh—grew bold: Gao, Peng, and Luo. They told the countryside that lawless men could take what governments would not protect. They moved like a stain, at once petty and cruel. In one cold night, their hands broke into his house. Lin Shen fought by the rule his father had taught: with improvisation as your ally. He used the splintered chair, a thrown pot for distraction, the very threshold of his home as a lever. He killed a man with the practiced precision of discipline loose from ceremony, and the act left him with neither triumph nor clean peace—only the heavy, rusted truth that the world would not stop asking for more. When the men left, they had taken the book with them in the jostle of the raid. It was like having the last thread of a tapestry torn from one’s hands. Lin Shen spent nights with fingers slick on oil, feeling the absence of what had once been warm and true as if he had lost a limb. He kept training in the dark. The frost took the shoulders of his young frame and left him with calluses as if to proof him against the future. He set snares, he studied the tracks of beasts, he learned to bind a rope with a hand that moved without thinking. Hunger sharpened his faculties into a new instrument. He moved through the months like a man learning to survive on a diet of small, precise choices: when to approach and when to lie low, when to strike and when to leave the blood to congeal in silence. And then the world decided to see how much he could bear. A note, pressed through the crack of a door like a verdict, demanded he leave. Intimidation, not argument. He tacked it to a wall as if posting a small law. He read it three times and the letters did not rearrange themselves into mercy. The bandits came again—bigger, angrier, with more hands for demolition. Doors were battering rams. The town that had once given him humanity gave instead to the currency of fear. Men who had been neighbors slowly bared teeth rather than hands when the struggle touched their thresholds. In the last tempest Lin Shen faced, the night was a blanket of gray with no stars. Men came with practiced cruelty; their attacks were a choreography of violence. He stood with his subordinates—three youngsters who had learned under his direction, their eyes still large and undulled—and together they met the raid. The skirmish tasted of blood and iron and the unpredictable geometry of desperate men. The sound of combat is a language without dialects. It rang out in small, terrible syllables: a snapped twig, a grunt, the metallic ring of a blade finding bone, the slick whisper of gore on cloth. Lin Shen moved as his father had taught him to move when improvisation is law: he used a fallen beam as a pivot to upend an enemy’s balance, found a broken spear and used its shaft with both hands so that ambidexterity became a doubling of force. He turned his left to a right without ceremony, and enemies who had planned for the expected found their plans unglued by unpredictability. His subordinates fell like struck reeds. One, a lanky youth named Bo Jian who had a laugh like boiling water, took a blade across the shoulder and went down with his hand pressed to the wound as if to hold back the shape of it. Another, young Han Jun, a solid man with the rough hands of someone who could mend a cart, had his thigh shattered by a cleft of iron. Their faces, in their last seconds, were not clouded by the world’s betrayals. They were simple—consternation at pain, the quick flash of fellowship, a regret at all the things one does not say before the light moves out. There was a fierceness to Lin Shen that the world would later remember, but in that moonlit scrub it had the shape of necessity. He executed a series of moves that later would be inked in memory as reckless brilliance: a feint to the right with his left hand while his right elbow arced in a surprising cross, a low sweep that caught an enemy mid-lunge, an improvised throw using the sling of a cart that slammed a man hard into a stump. He moved like someone who had been taught to shape the environment into the weapon of his choosing. In the end he stood alone amid the smoked-out ruins of the encounter, his breaths thin as a bell’s toll. Two men lay broken and still; black stains darkened the leaves beneath them. His own body had become a ledger of punishment: ribs that answered each breath with pain, a shoulder that hung like a poorly-strung lattice. Yet a small, stubborn flame of absurd pride burned in him—he had protected what he could, he had made his skill mean something. It was then, when the world narrowed to the distribution of breath, that he saw the shadow. Not tall—tallness is a human measure—this figure was a blot of absence under the moon, draped in garments that refused to give edges. The air around it felt different, thick as if the night had pressed itself onto his skin. The figure’s appearance was not accompanied by a sound but by a weight: the sense that some new law had shifted in the world’s statute. “Lin Shen,” the voice said, and the name arrived calibrating his bones. It was not a voice from the throat so much as a current through the marrow. His last faculties insisted on stubborn normalcy. “Who are you?” he asked, though his mouth tasted of iron and his limbs protested with the honest rebellion of defeat. The figure did not answer with a name. It laid a thing into his hand—brown as old bark and small, as if some origami of fate had been folded for him alone. The leather-bound book. For a breath the world became a careful, precise geometry of infinite tenderness and infinite cruelty. Lin Shen clutched the book as a drowning man clutches the last plank. “Do you understand exchange?” the figure asked then. Its words were not cruel but they were not friendly either. It spoke as one who cataloged balances. “I… I do not bargain with shadows,” he managed, though his voice was a thread. “You bargain every day with life,” the figure replied. “You spent leather and sweat; you paid with blood and loss. A life is but an entry. Will you add another line?” The idea was savage and simple. Offerings to such a thing are never wholly clear. Before the last moment the soldier in him—conditioned to decency in action, not sentiment—made a decision that felt like both logic and prayer. He closed his fingers around the thing the figure extended, felt it pulse faintly like a heartbeat, and understood that the moment for refusal had already passed. Darkness accepted him like an old debt. When he opened his eyes, the world was different. The change was not merely physical but instrumented in every sense. His skin felt thinner in a way that made breath loud; his limbs took on a softer awkwardness. His teeth did not bite with the habitual grit of a man hardened by years. Confusion was a small, sharp bird in his chest. He blinked against the bright absence of direct sunlight—the roof above him slatted and the light came through in stripes. He was in a wooden cage, the smell of sweat and stale bread thick and almost suffocating. Sounds—small, human—murmured around him: a cough, a child’s whimper, someone sobbing in a hush. There were other cages, clustered under a low rafters’ roof, the whole place smelling of commerce and hunger. Panic surged like a flame in his throat and he rose in something close to a bound that showed more practiced reaction than the years of a child. He placed his palms against the bars and felt metal bite his skin; they were thin and cold and the motion made his muscles protest in a youthful way. A laugh escaped him—high, surprised, and brittle. He had no right shoulder to bear with the same steadiness as before. He had not been given an old soldier’s body but a boy’s—fourteen years old, the number an absurdity and a wound. Around him the captives moved like a slow, pained tide. Eyes pinned to him—curious, tired, wary. A girl about his age sat with knees hugged to her chest; her face was thin and her eyes were like knives tempered in silence. An old man with a beard more white than hair hummed old verses under his breath. A small, wiry boy whose ribs showed worked his jaw as if chewing anger into something useful. “Slaves,” the boy called in a small voice that sounded foreign to Lin Shen’s inner ear. “Picked up near the road. Market day soon.” It took a breath to acknowledge the word as if the syllable itself carried a new weight. Slaves. The notion slipped into him like a sled into snow: solid and terrible. The leather book—the thing the figure had given him in the forest—lay not in his hand but in a place behind the membrane of memory, like a candle under a jar. He could sense its presence, the echo of its lessons, but not its leather. The knowledge, however, had lodged in his marrow. He could still recall the arc of a wrist lock, the feel of a sweep’s timing. The body had changed but the mind had not entirely forgotten. The depot swarmed with those who trafficked in human commerce. Men in rough coats, faces like stone tablets, shuffled through the aisles. Their laughter had no softness; their tasks were the registry of profit. A scarred man with a long white line across his cheek—Zhao Rui—strode in with a gait that spoke of someone for whom cruelty was a craft practiced to perfection. His eyes assessed the cages like a merchant rates bolts of cloth. Bai Kuan, a merchant with the soft thread of polite speech and the hardness behind it, came behind, running his fingers over wrists and chins and the shoulders of the captive as if he were measuring the worth of a horse. He made small notations on a blackened ledger and smiled like a man at a private joke. Around him, men with the arrogance of those whose hands are never called to honest labor cracked whips against the rafters. The Three Brothers—Gao, Peng, Luo—moved like clichés made flesh: rough, cruel, and practiced in the pleasure of a quick break of someone else. Lin Shen’s first contact with the depot’s men came in the form of a shove. A small boy—Xiao Bao—defied a slaver’s touch, and hands descended to punish him for insolence. Small flames of resistance flare in such prizes sometimes, and Xiao Bao ran at the man with a broken piece of a wooden plank. The slaver laughed at the audacity and raised a boot. Before he could put that boot down, Lin Shen—a shell of a boy but with a soldier’s observation—acted by muscle memory and the scraping of instincts. He wedged his shoulder into the bars, used his frame as a pivot, and shoved with a force surprising for his apparent age. The slaver staggered and fell with a clatter that hushed the room for an instant. For an ephemeral moment, the depot was an animal holding its breath. “Youngster!” Zhao Rui bellowed, annoyance reddening his face as he recovered. He strode forward and, with the confidence of one used to breaking others, reached through the bars to seize the boy’s chin. His fingers were like clamps, intrusive and owned. “Name?” the slaver asked, as if names were ledger entries. “Lin Shen,” came the answer—thin, decisive. It felt like a small bell struck in a nearly abandoned hall. Zhao Rui sneered. “With a name like that, perhaps your price will be higher.” He grinned in the way a man smiles when he is certain the knife will sell. He smacked the bar with his palm, enjoying the sound. Somewhere in the cages a woman sang under her breath to still a child’s fear. Old Zhang—the gray-bearded scholar-like figure that had been passed about the cages—muttered a verse about brokers of human doom and marked the sound of Lin Shen’s voice like a coin he had not yet seen. Mei Hua, the quiet girl whose eyes were quick as a hawk’s, watched the new boy as if reading his palms. There are faces that betray the presence of more than one life in them; Old Zhang’s was one such face. He saw things in the bones of men and cats and in the way a child’s jaw clenched that others did not. The depot stormed into a small violence. Men struck with whips, gripped by the ease of a practiced order. A slaver tried to teach Xiao Bao his place and the boy snarled and struck back with a swing that deserved better. The Three Brothers moved to punish him with the muscle of rage. For the price of showing defiance, many of the cage’s children would pay hard. Lin Shen did not step between every blow. He had learned restraint under his father’s hand. Strength revealed itself not as a series of heroic acts but as the quiet management of danger until the right opportunity flared. Yet when a slaver raised a wooden rod to strike Xiao Bao cruelly, the boy’s small face contorted and the world’s blood rose in Lin Shen as if a spring had been pierced. He lashed out through the bars with a practiced twist, grabbed the man’s wrist, and with a motion that spoke of years of applied leverage he snapped it. The man howled and dropped the rod like a broken bell. That instant gave the captives a breath. Old Zhang clapped a hand to his mouth and wept softly; Mei Hua’s eyes widened and then softened in an unreadable way. The slavers, enraged at their bruised pride, rallied. They were not men of much honor, but they were men practiced in restoring the order of cruelty. Fear and beatings followed; ropes were pulled taut and wrists found new ache. When the chaos subsided and the depot resumed its humming of bartering and list-making, Zhao Rui glared at Lin Shen with a look that was less anger and more an effort at calculation. “He fights like one trained,” he said to Bai Kuan, who smiled and set down his ledger with a thoughtless grace. “Keep him—some buyers will prefer spirited stock.” It was an admission of utility, not worth. He did not know yet whether to see Lin Shen as entertainment or as danger; a spirited captive could fetch a higher price if broken properly, or, if left untamed, cause losses. Lin Shen lay awake that night on a pallet of straw, the depot’s breath moving like a tide in the rafters. He turned the motion of his body slowly, feeling the aching of ribs that were not yet broken nor yet healed. His memories—harsh and bright—rolled like tide-lines. He saw scenes with the sharpness of someone who has been honed by experience: his father’s hand pressing his elbow, the way a cart’s axle could be used as a lever, the burning taste of blood at the corner of the mouth. He tasted the forest’s iron and the figure’s silence. The bargain he had made remained a mystery folded into his bones. Mei Hua came to his bars without sound in the last hours, her movement that of a practiced shadow. She had a small scrap of bread, offered with a trembling hand. “Eat,” she whispered. “Do not look at me. If they see pity, they will sell it for coin.” Lin Shen took the bread with a caution he had not known he could still feel. The warmth of it in his mouth was a small, private miracle. He watched the girl’s face—sharp angles softened by hunger—then he gave her a look that was equal parts gratitude and calculation. She turned her head away, hiding the quickness of emotion, because in that place to be seen was sometimes to be priced. Old Zhang, who kept to himself but had the habit of watching as a scholar watches a text, said in a small voice that seemed older than the rafters, “You are not like the rest of them, boy. You bear an old tune.” Lin Shen considered the phrase. “An old tune,” he repeated. The memory of his father’s lines—“Martial skill is a language of the world; learn the silence between words”—settled over him like an old coat. In the cramped and filthy depot it was easy to believe that the whole world had become a narrow ledger of trades and bargains. Yet within that ledger, within those small exchanges, a man could begin to gather another kind of wealth: knowledge, patience, the shaping of will. When the gray of dawn leaked through the slats, the depot emptied with the clatter of men preparing wares. Buyers would come with their ledgers and their cold smiles, and people like Bai Kuan would judge the currency of human flesh with the same lightness as they judged fabric. Lin Shen watched the men leave and felt the small, mechanical motion of his breath. He had been given a second life at a cost he did not yet understand, in a body that begged for nourishment and which would need to grow into the shape of danger again. He made a promise to the small circle of souls within those cages: not a shout of vengeance, but a plank of will laid quietly. He would learn this world’s measure and bend it. He would make the knowledge of the leather-bound book his, even if it was lodged for now like a seed beneath his tongue. He would not be sold wholly as a thing nor made to bow forever to the ledger. “Father,” he murmured to a sky that did not hear, the name sounding small in the rafters, “I have been given more time. I will not waste it.” There is a hardness that comes when a man has been taken to the roots of pain and offered a new graft. It is not always a sword. Sometimes it is a patient counting of breath and the steady, careful practice of small arts. Lin Shen lay awake and counted breath—one, two, three—letting the rhythm of his name return like a tide. The depot’s sounds became a lullaby for the kind of resolve that does not glitter: the chorus of feet, the rustle of ledgers, the soft complaining of straw. Outside, the world turned with the indifferent precision of seasons. Inside, in a cage beneath the moon and the rafters, a boy named Lin Shen folded his hands, practiced the first, secret motions of Tracesong Craft he remembered, and listened to the echo of a shadow’s bargain beat inside him like a second heart. Thus, the first night of his second life passed itself over him like the slow turning of a page. What had begun as an end had become the opening of a long, slow work: to learn, to survive, to shape memory into instrument. Unknown to those who bartered and laughed and ruled by ledger, a storm had started beneath one thin chest. The world was not yet aware that in the cramped geometry of a slave depot something sharpened like a blade.

5 months ago